Measles: The Local Effort

“Many or most public health issues are inherently local, but the federal government still has an important role to play, and they have resources to bare when needed,” said Chrissie Juliano, Executive Director of the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC). On September 23, 2019, the BCHC and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), a Research!America member, addressed this topic in a briefing titled “The Measles Outbreaks of 2018/2019: Perspectives from Local Communities.” At this event, along with Ms. Juliano, spoke Dr. Colleen Kraft, Immediate Past President of AAP; Dr. Oxiris Barbot, Commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; and Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser, Chief Medical Officer of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Measles is a highly contagious virus that, before a vaccine was developed, affected over three million people a year in the U.S., explained Dr. Kraft. Since the introduction of a vaccination program in the 1960s, however, she said there had been a 99% decrease in measles cases. Nonetheless, a recent resurgence of this disease has occurred, largely due to vaccine misinformation and a hesitancy of many to obtain the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine.

In her presentation, Dr. Barbot focused on about the recent measles outbreak in New York City mainly affecting ultra-Orthodox communities, which occurred largely due to misinformation campaigns targeting these groups. Responses such as engaging local community members and leaders were key in tackling the outbreak. For example, the Jewish Orthodox Women’s Medical Association formed during this time and allowed physicians who were trusted by these communities to speak with and treat vaccine hesitant individuals. Public education materials were also distributed in English and Yiddish to address the myths spread by anti-vaccine groups. Due to a combination of these efforts and more, the measles outbreak in New York was declared to be officially over in September 2019.

Dr. Gunzenhauser, meanwhile, described the several measles outbreaks that have occurred over the past few years in Los Angeles; those outbreaks were more varied in origin. He stated that “herd immunity” (when the immunization of most protects the few who cannot receive vaccines due to health concerns) was a major factor in ending these outbreaks. Additionally, several California laws, such as one to end religious and personal-belief exemptions to mandatory vaccinations, have aided in increasing vaccination rates.

Many of the public health responses in these cities were local but could not have been conducted without support from the federal government. Ms. Juliano emphasized four key sources for “reliable, dedicated funding” at the federal level: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s immunization program; the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases (ELC); the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) funding program; and the Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF). Additionally, Dr. Kraft highlighted a recently introduced, bipartisan bill, the VACCINES Act of 2019 (H.R. 2862). This bill would promote research to better understand vaccine hesitancy, establish an “evidence-based public awareness campaign” on vaccines, and allow for data collection on communities being targeted by misinformation campaigns. As Dr. Kraft stressed, “Our enemy is the disease. The way we combat this enemy is by education and vaccination.”

For more information, check out Research!America’s fact sheets on vaccines and infectious diseases.

This blog post was written by Anna Zavodszky, a science policy intern at Research!America. The Science Policy Internship is supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

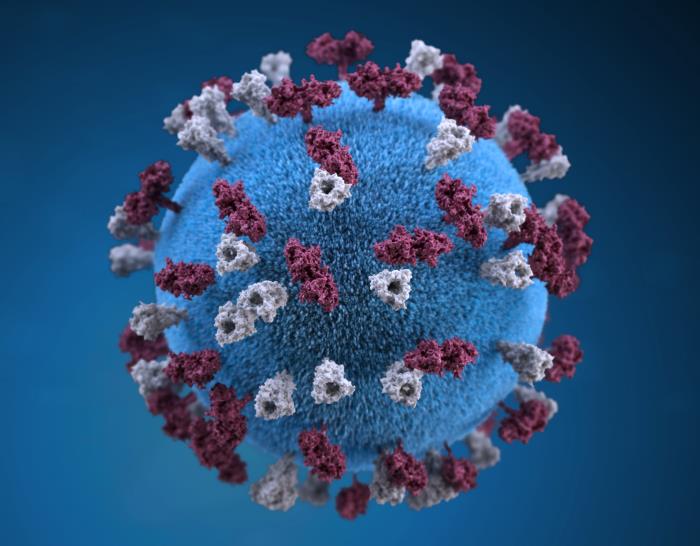

Image Credit: CDC/ Allison M. Maiuri, MPH, CHES. Illustrator: Alissa Eckert. This illustration provides a 3D graphical representation of a spherical-shaped, measles virus particle that is studded with glycoprotein tubercles. Those tubercular studs colorized maroon, are known as H-proteins (hemagglutinin), and those colorized gray are referred to as F-proteins (fusion). The F-protein is responsible for fusion of virus and host cell membranes, viral penetration, and hemolysis, and the H-protein is responsible for binding of virus to cells. Both types of proteinaceous studs are embedded in the envelope’s lipid bilayer.